We grope for the wall like the blind, and we grope as if we had no eyes: we stumble at noonday as in the night; we are in desolate places as dead men."

Isaiah, 59:9-10

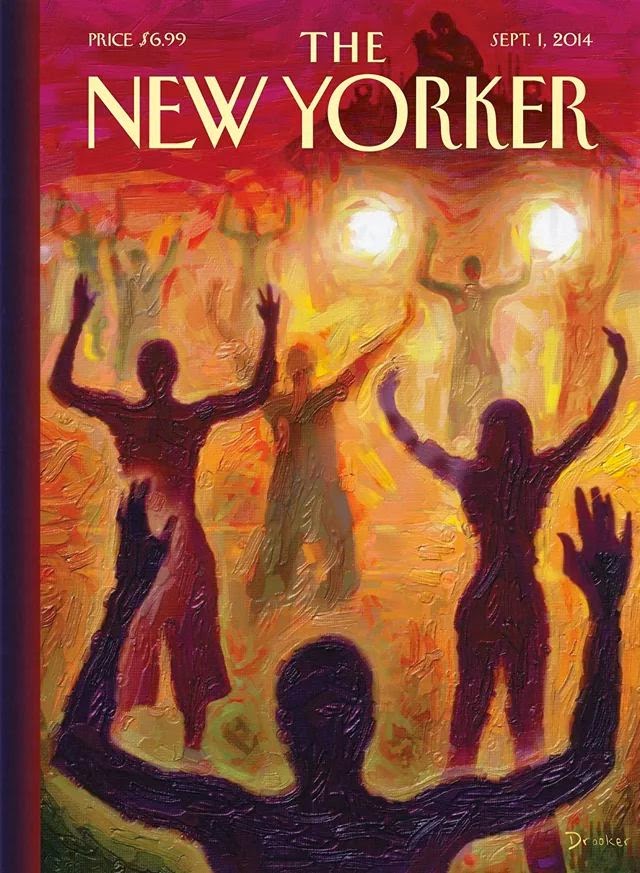

More than two weeks ago, a white cop in Ferguson, Missouri shot an unarmed black teenager six times, leaving him lying in the middle of the street in a puddle of blood. Since then there have been largely peaceful demonstrations, some riots, and looting - all because of a common perception of a racially-motivated police action and a justice system blind to police misconduct. And we're right back, it seemed for a while, where we were throughout the civil rights marches of the 1960s.

Journalists can offer us comparisons with other times in American history when black people took part in violent riots. The rioting was usually sparked by some incident and they were usually divided along racial lines. There was a time in American history that is still so painful that few people even know what happened. It was the time, on April 4, 1968, when Martin Luther King, Jr. was murdered. Three British journalists, who had been assigned to cover the election for the London Times, were there when the news broke across America like an enormous storm. In the book that was published the following year, (1) they wrote:

"By the end of the week, thirty-seven people had been killed and there had been riots in more than a hundred cities. For the first time in history, the situation room in the basement of the west wing of the White House was plotting the course of a domestic crisis. Into that Nerve center of America as a great power there flowed reports of fighting - not in Khe Sanh or on the Jordan, but on Sixty-third Street in Chicago, One hundred twenty-fifth Street in New York, Fourteenth Street in Washington: the White House is on Sixteenth Street. . . .

And there was Robert Kennedy. When he heard that King was dead, he went out onto a street corner in Indianapolis and told the small crowd of Negroes [sic] who gathered what had happened. Standing under a street lamp, he waited until the shouts of the men and the wails of the women had died away. Then he quoted Aeschylus . . ."

The speech that Kennedy delivered that night was lost in the crush of media coverage of the aftermath of King's death. It took his deeply-felt and profound words to capture the lesson that Americans failed to learn then.

"Ladies and Gentleman - I'm only going to talk to you just for a minute or so this evening. Because I have some very sad news for all of you, and I think sad news for all of our fellow citizens, and people who love peace all over the world, and that is that Martin Luther King was shot and was killed tonight in Memphis, Tennessee.

Martin Luther King dedicated his life to love and to justice between fellow human beings. He died in the cause of that effort. In this difficult day, in this difficult time for the United States, it's perhaps well toask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in.

For those of you who are black - considering the evidence that there were white people who were responsible - you can be filled with bitterness, and with hatred, and a desire for revenge.

We can move in that direction as a country, in greater polarization - black people amongst blacks and white amongst whites, filled with hatred toward one another. Or we can make an effort, as Martin Luther King did, to understand and to comprehend, and replace that violence, that stain of bloodshed that has spread across our land, with an effort to understand, compassion and love.

For those of you who are black and are tempted to be filled with hatred and mistrust of the injustice of such an act, against all white people, I would only say that I can also feelin my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man.

But we have to make an effort to understand, to get beyond these rather difficult times.

My favorite poet was Aeschylus. He once wrote: 'Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart, until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.'

So I ask you tonight to retyurn home, to say a prayer for the family of Martin Luther King, yeah that's true, but more importantly to say a prayer for our own country, which all of us love - a prayer for understanding and that compassion of which I spoke. We can do well in this country. We will have difficulties. We've had difficult times in the past. And we will have difficult times in the future. It's not the end of violence; it is not the end of lawlessness; and it's not the end of disorder.

But the vast majority of white people and the vast majority of black people in this country want to live together, want to improve the quality of our life, and want justice for all human beings that abide in our land.

Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of the world.

Let us dedicate ourselves to that and say a prayer for our country and for our people. Thank you very much."

Robert Kennedy had quoted poetry before. In his speech before the Democratic National Convention in 1964, he made a crowd of rowdy party delegates weep when he said: "When I think of President Kennedy, I think of what Shakespeare said in Romeo and Juliet:

"If he shall die takehim and cut him out into the stars and he shall make the face of heaven so fine that all the world will be in love with night and pay no worship to the garish sun."

I won't dwell on the unlikelihood of a politician today telling a crowd that his favorite poet is Aeschylus, but what Robert Kennedy spoke about on that awful night so many years ago was making an effort, of doing something difficult, of trying to understand instead of simply giving in to hatred and reacting to an apparently inexplicable act of violence with more violence. We have to choose, while we still have the power to choose, in which direction we as a people want to go.

(1) An American Melodrama, by Lewis Chester, Geofrey Hodgson, and Bruce Page.